The Railway to Nowhere

The Railway to Nowhere

Y Shed was officially opened in October 2019, a fitting date because it was exactly 150 years ago since the railway from Prestatyn to Dyserth was completed. Y Shed was the name chosen by Grŵp Cynefin as a Communities Action Initiative instigated by the Meliden Residents’ Action Group. The name and obligatory logo was was a sort of branding exercise because the building at Pen y Maes was in fact a railway goods warehouse and not an engine shed—the engine shed was in Rhyl.

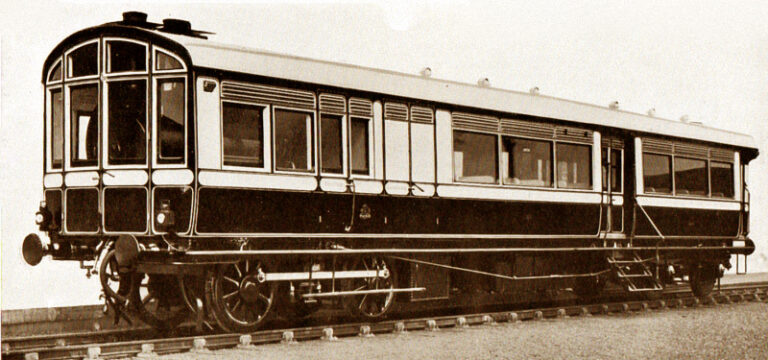

The famous Indian Summers of the Edwardian period witnessed remarkable activity between Prestatyn and Dyserth—all made possible by a novel new kind of railway carriage which had a small steam locomotive installed inside it at one end. Passengers were carried in two compartments that each seated 24 and there was a guard’s compartment which could carry luggage in the middle. The driver was in a compartment with remote controls at one end, like a modern diesel carriage and the fireman was at the other end with the built-in engine. The railway company called it a Steam Motor Railcar, the people of Meliden called it The Motor. It wasn’t a train—it was a tram with reversible seats and it even had a conductor to collect the fares..

The Motor was intended to be ready for August 1905, to take advantage of the increasing number of holidaymakers who wanted to visit Dyserth waterfalls but the manufacturers had problems and so it did not arrive at Rhyl until the end of August. “Too late for the holiday season and doomed to failure,” you might think. Apparently not, in the first month it carried 14,612 passengers! Very strange.

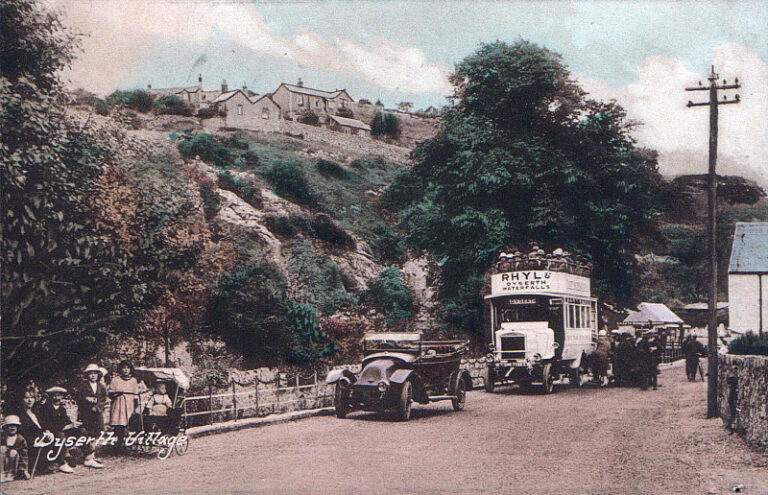

Most were holiday makers from Lancashire, who had been visiting Prestatyn and Rhyl since the mid 1890s, creating a Little England to which they returned year after year—many finally settling in this area. Most of all they wanted to see the sea and the mountains but Dyserth Waterfalls was also on their to-do list. Surely they must have been disappointed when they alighted at Pandy in Dyserth to find that it was two-thirds of a mile away along unmade roads, or half a mile away along footpaths—with a good chance of becoming lost. The people of Dyserth were not to be defeated and each Motor was met by hordes of boys with cries of, “Take you to the waterfalls Mister?” Others walked around with placards advertising their mothers’ newly-opened tea rooms, whilst their fathers and elder brothers badgered the better off visitors with offers to taxi them down the hill in a motley collection of old broughams, shays and dog-carts. [It reminds me of Rhyl station in the old days when on Saturday mornings, the constantly arriving trains brought thousands of visitors who needed to find the lodgings they had booked for their week at the seaside. Some taxi drivers were unwilling to carry them such short distances to places like River Street or Butterton Road so the local lads with their home made handcarts used to descend on the hapless visitors with fixed-price offers to take them and their luggage to anywhere in Rhyl—on foot!]

The truth was that the railway company was only testing its new steam tram along a nice quiet stretch of railway and had no intention of running a permanent service. Once everything was sorted out, the service would be closed without too much bother and the motor railcar transferred to a busier and more lucrative route along the coast. That is not what happened!

The number of passengers it carried during the first month surprised everyone and the success was put down to novelty and the fine weather during October 1905. The timetable was useless for anybody to get to work because the first motor from Meliden left at 9.50 a.m. but it was soon changed to 8.25 to connect with the coastal railway services. That may not seem exciting now but it was the most important thing that had happened since the lead mine closed twenty-one years earlier. It became possible for people to work much further away from home and money started coming into Meliden—all the empty houses started to fill up—and they were not local people. Our village was never the same again.

Within a month, the price of land in Meliden and Dyserth doubled! Speculative builders appeared from nowhere and urgently sought land. Typical was the story of a would-be builder who had expressed an interest in buying land from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners who were selling at £50 per acre but the sale fell through. After second thoughts, he reopened negotiations, only to be informed that they had since received offers of £100 per acre. He paid without protest! Dyserth became a building site but Meliden was not yet affected quite so much because neither the Bishop nor Lord Mostyn were releasing land—yet! There were other landowners who were willing to sell and Station Terrace was built followed by the houses at Pen y Maes. Land on either side of the road from Sandy Lane to the Ffrith was snapped up and houses were also popping up between Melyd Avenue and Woodland Park Bridge.

There were never motors on Sundays or Christmas Day but otherwise it was business as usual and on Boxing Day 1905 the whole of Meliden and Dyserth decided to go to Prestatyn! The make-shift wooden platform at Pen y Maes was besieged for the early morning motor because it was connecting at Prestatyn with a special cheap train to Chester. When it called at Meliden, all 48 seats had already been taken and the conductor would only allow 22 more standing—that still left 40 on the platform. The situation became rather fraught until a rumour spread that the motor would come back and peace was restored. The motor left and everybody waved then waited—and waited—but they were disappointed.

At the start, there had been 8 return journeys each day. In 1906 this was increased to 14 but even that was not enough and Easter Monday saw extra motors laid on. The platform at Meliden was too small to accommodate the number of people wishing to travel and the timetable had to be abandoned. In true tram fashion, it became a shuttle service as it hurtled up and down—not, in theory, exceeding the light railway 25 m.p.h. speed limit—in a frantic attempt to move the crowds. It was possible only because it was a holiday and there were no limestone trains running. The Prestatyn to Dyserth Railway was running more services than the Vale of Clwyd line which connected Rhyl with Denbigh!

This success did not go unnoticed by the Brookes Brothers of Rhyl who still used horse-drawn vehicles such as their well-known Tantivy which was a charabanc with several precarious, high up rows of seats, all exposed to the weather. Tantivy is an old word for a rapid gallop or ride and it certainly was pleasant and exhilarating on day trips but not for a regular bus service which would have to run to schedule in all weathers—including going up Dyserth Hill. It would be another four years before the enterprising Brookes Brothers became White Rose Motors with motor buses. There was also at that time a small Chester company starting to run motor services into Flintshire—Crosville! The threat from road transport was serious..

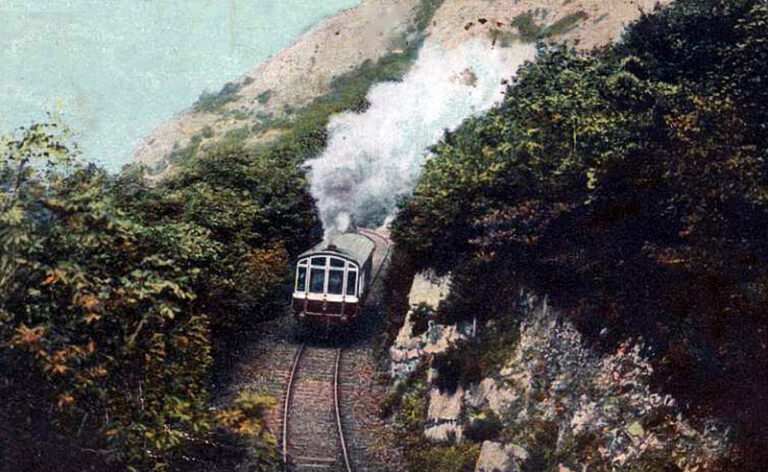

So long as the number of passengers travelling up from Prestatyn never exceeded the seating capacity, the motor coped—but only just. The driver, Dan Jones of Rhyl, known as Dan the Motor Man always worried about the first half mile up to Fforddisa Bridge. A really steep climb, his regular fireman, Sam Bentley would stoke the boiler to its limit before they left Prestatyn station and then, by means of a vigorous departure, Dan usually reached the first stop at Chapel Street which was behind present-day Pendyffryn Gardens where you can still see a little section of railway track. Starting off from here was always a problem in the rain when the track was slippery but with very delicate use of the regulator, Dan could reach the top at Fforddlas bridge and then on to Woodland Park, or Rhuddlan Road Halt, as it was known, without stalling.

Never designed for that sort of treatment, the motor became a constant and expensive battle to maintain. By 1910 it was a mechanical wreck and so the company built a Mark 2 version—bigger and better with a more seats, it was powerful enough to pull a carriage when needed. This was ideal for holiday times when the tram could become a train. There were many other changes and improvements over the years. Additional halts were added—the Golf Club—Allt y Graig for the Merseyside Holiday Camp children—there were late night theatre trains to Rhyl, specials to picnic at Marian Mills, shopping specials and Sunday School and club outings. On one occasion, the Prestatyn Urban District Council held a meeting of its Water Sub-committee in the motor as they travelled to inspect the waterworks at Marian Mills! It was quite normal to carry 1,300 on an ordinary day in June and 2,000 on a bank holiday. Local people used it as a means to connect with trains to work in Liverpool and Chester. It proved invaluable during the First World War when many of the population of women went to work in the munitions factories on Deeside.

Even the Mark 2 motor struggled with the hills and by 1918, poor wartime maintenance was resulting in regular breakdowns—usually just above Lady’s Wood. The White Rose Motor Company started tempting railway passengers with their nice new motor buses which stopped more frequently on routes that passed their doorsteps. Very convenient.

In 1922 the railway company decided to pension off the motor but its replacement was no ordinary train—it was a push-pull. The front carriage had a driving compartment with all the basic controls and a bell communication system to the fireman who worked alone in a small, specially adapted steam locomotive. The carriages were always pushed up to Dyserth and on the return journey to Prestatyn, the driver joined the firemen on the footplate of the engine. It was faster accelerating and more powerful than the old motor which it gradually replaced from 1922—but not so popular. The old motor had been quite luxurious with compartments fitted out in fine wood but the push-pull was spartan by comparison—with woven cane seats!

By the late 1920s, the train was travelling almost empty—the buses had won. In 1930, the August 16th edition of the Prestatyn Weekly reported a rumour that the passenger service was to end and on the evening of September 30th, the last train left from Dyserth. Did the railway company worry? Not in the least—it had already bought the bus company! The Railways (Road Transport) Act of 1928 had allowed the Company to start running its own bus services but instead of building its own fleet, it purchased several existing bus companies—which, of course, included their passengers. First, it acquired the Crosville Motor Company of Chester and then a number of smaller companies along the coast, including White Rose Motors.

And there ends the story of the motor and the push-pull train that served the hill-folk and their visitors for 25 years. You would have been born before 1922 to have travelled on the motor but there is still a handful of people who remember the push-pull train. People used to talk about the motor with a sense of loss and of having been abandoned—but it was they who abandoned it.