A Drinking Problem at St. Melyd’s

A succession of Acts of Parliament which had been designed to control drinking on Sundays had created several loopholes—the most famous was claiming to be a bona fide traveller. Anyone could tell the landlord that he or she was travelling and the only onus lay on the traveller to tell the truth, the landlord was expected to believe it—hence the good faith epithet.

Henry Jones, an ex-miner, rented the house next to the railway warehouse at the top of Meliden Maes from about 1866. His ambition to escape the mine fulfilled, he became a coal merchant and opened his front room as a licensed beer parlour called The Miners’ Rest. In 1885 he was summonsed for being open at 9.45 on Sunday night on April 12. P.C. Edward Jones had caught Roger Williams, Henry Lewis, and Robert Thomas with pints in their hands. They showed no sign of guilt—especially Robert Thomas, who continued to drink. The landlord saw P.C. Jones the next day and offered him a golden sovereign to overlook what had seen. (That would be about £105 now.) P.C. Jones refused and so the landlord told him a hard-luck story in the hope he might drop the charge. He said that three men had arrived with a message from the owner of a nearby farm concerning some animals which had strayed onto the landlord’s land. The drink was offered as a reward and no money changed hands.

In court, the story had changed. They agreed that it concerned a field full of sheep somewhere near Rhyl—but that was all they would agree on. The men all had different versions, so eventually the court decided that the landlord was telling the truth and the charge was withdrawn but two of the men were fined 5s with 8s. costs for being on the premises illegally. The third man, Robert Thomas got off because he was able to utter the magic words—bona fide traveller. It was true, he had walked over five miles from Trefnant and that made him immune from prosecution.

Drinking on Sundays was commonplace and the country lanes teemed with walkers. Men from Meliden walked to St. Asaph and would pass men from St. Asaph who were on their way to Dyserth. Although not actually enshrined in law, the accepted walking distance was three miles. The landlords of Dyserth were lax and famous for their faith.

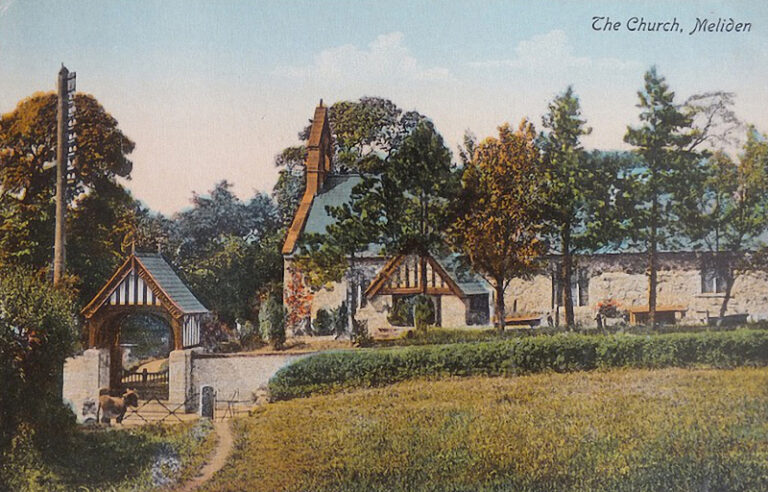

The strollers from Rhyl were in the habit of spending all Sunday afternoon drinking in Dyserth and then returning the scenic way, visiting pubs in Meliden on their way home. On the evening in question a small group of about five of them had commenced their usual game of pitch and toss in the lychgate and yelling coarse abuse at the vicar and church wardens but since there was no policeman in the village it had to be endured. This night was different because, almost unseen, down by the Vicarage P.C. James Taaffe, with his bicycle, lay in wait. When the men came down the hill, he told them to go home. William Delaney threatened to kill him and was arrested. The other men told the P.C. that they would they would also kill him unless he was released. They attacked the officer but he was able to deal with them and they fled—leaving behind their ringleader, whose legs had stopped working.

In court, Delaney explained that they had been for a walk and on their way to Prestatyn they were met by a constable on a bicycle, who, without saying anything, got hold of him and assaulted him with his truncheon. Then his companions were assaulted.

They had not reckoned on Ann Jones of Tai Cochion, the celebrated Meliden gossip who had seen P.C. Taaffe’s manoeuvres through her lace curtains and after waiting for the Rhyl men to go down the hill, she followed, gathering an eager crowd as she went. They witnessed the whole affray and gave evidence in court that the constable did not assault anybody. Even without their evidence, the magistrates knew the men were lying because it was common knowledge, in Meliden and Prestatyn, at least, that P.C. Taaffe never carried a truncheon. An open and shut case, they were fined heavily and attendance at the evening service improved, hopefully.