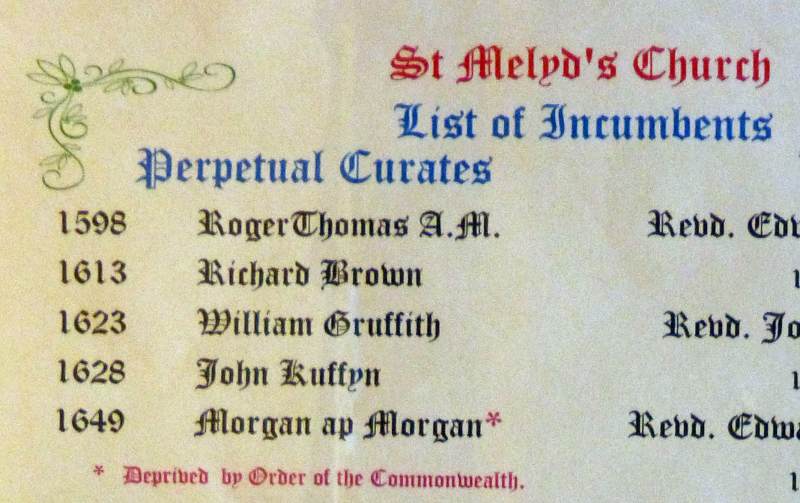

The incumbents’ list in St. Melyd’s porch stretches back to 1596 but one stands out—Morgan ap Morgan 1649, deprived by order of the Commonwealth. Not our present-day Commonwealth but the name for England and Wales, Scotland and Ireland at the time of Oliver Cromwell. So why was Morgan Morgan sacked?

Our country was at war with itself—the ‘English’ Civil War. The 90,000 deaths from fighting and disease on the mainland and 600,000 in Ireland have almost been forgotten here—but not in Ireland. King Charles I was served by a Parliament that wanted more power but he wanted to rule without it and since only he could call Parliament, it seldom met. There were disagreements but it was the King’s insistence that he had divine right to rule, including matters of religious doctrine that proved to be his undoing. Parliament would not accept and fought a war against the King and his army led by the ‘Cavaliers.’ The Parliamentary side won and after a trial in 1649, the King was executed for treason. A new Parliament was set up but it was dysfunctional so Oliver Cromwell closed it in 1653. He adopted the title of Lord Protector and ruled as dictator with the support of his ‘Roundhead’ army.

King Charles believed in Episcopalianism, whereby the monarch is the head of the Church with the Archbishops and Bishops beneath at the next level. This was different from Presbyterianism, where Our Lord is head of the church and each congregation elects elders to lead the worship. In Presbyterianism, the Minister is one of the elders and once a year each congregation sends its minister with one elder to a Synod to make decisions. King Charles preferred Episcopalianism because he could more easily exercise his perceived divine right to control the Church. The Scottish churches did not agree, consequently he forced legislation to change matters without consulting the clergy or even the Scottish Parliament. He also tried to take possession of lands once owned by the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland. In 1638 he accused the Scots of treason because they protested about the new 1637 Book of Common Prayer which he and the Scottish Bishops had compiled for them. Resistance grew and the Scottish Bishops were thrown out—a war with Scotland was inevitable but Charles lacked money and his army was ineffective. The Scots went on the war-path and marched as far as Newcastle before he made peace with them. Charles even had to pay them £850 a day until they returned to Scotland! (£120,000 now.) It was the beginning of the end for Charles—his weaknesses had been identified by clever men like Oliver Cromwell.

Since the split from Rome in 1534, a century had passed and you would not have expected to find any articles of Catholic ritual in still in use but old habits died hard. In 1641 an order was issued ‘to deface, demolish, and quite take away, all images, altars and tables turned altarwise, crucifixes, superstitious pictures, monuments, and relics of idolatry, out of all churches and chapels.’ Soon after another order banned pictures of the Trinity, images of the Virgin Mary and all communion tables had to be cleared of candles and basins for holy water. Bowing at the name of Jesus or towards the east end had to stop. In 1643, vestments were sold off and religious images in public places became illegal. The sign of the cross on anything used in the worship of God was not permitted ….. ‘and copes, surplices, superstitious vestments, roods, fonts, and organs, were not only to be taken away but utterly defaced.’

It must have been at this time that the old St. Melyd’s font became infill for the Devil’s Door, the rood screen taken down and all the wall texts and images whitewashed over. Was this Puritanism at its height? Not quite—in 1645 the use of the Prayer Book was forbidden and all clergymen with Episcopalian beliefs were to be deemed unsatisfactory and ‘deprived’.